I’m sure we’ve all heard the “growing pains” diagnosis that is commonly given for so many lower limb non specific pain episodes in young children and adolescents. Whilst growing pains isn’t a totally inaccurate terminology, it’s the perception and management of these growing pain syndromes that needs to be improved. It’s so common in our physio setting to hear parents say “It’s only growing pains” because that’s what they’ve been told, but to ignore unexplained pain in children, especially around the hip, knee and heel can be at your own (and your child’s) peril.

Whilst the term “growing pains” isn’t totally inaccurate as mentioned above, the philosophy of “they’ll grow out of it” isn’t totally inaccurate either. For kids with true growth-related pains, the condition probably will burn itself out – but it may surprise to know that this often doesn’t happen in weeks or months: it can take years in some cases. And whilst it might burn itself out eventually, what other effects are there during this time in a young child? Not only the physical effects of trying to play sport in constant pain, but the psychological effects of not being able to join in with friends at school or at club sports. Sometimes I think we lose kids to sport because it just becomes too much to play in constant pain.

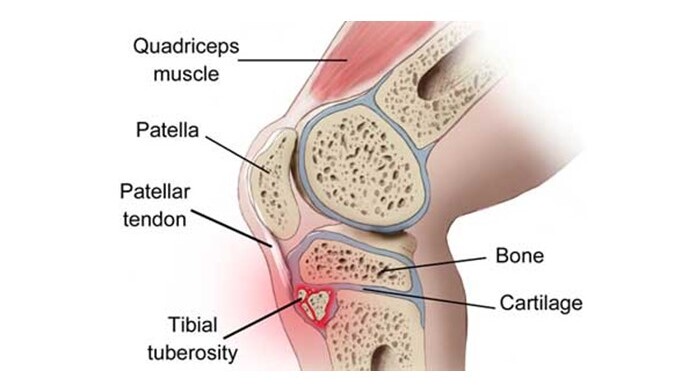

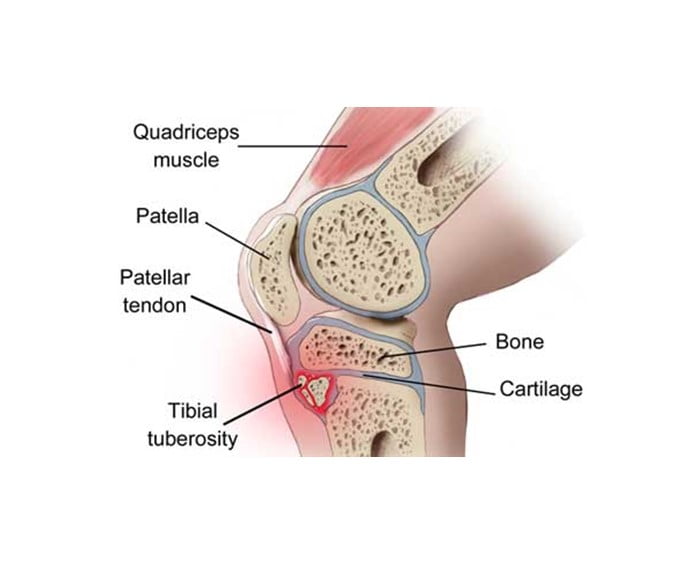

In terms of this eventual burn out philosophy, there’s some sobering statistics from some recent studies looking at a condition called Osgood Schlatters Disease (OSD) – an awful term because it’s not a disease, it’s a condition! OSD is a condition seen in growing, adolescent kids that is characterised by pain in the upper aspect of the front of the shin, just under the kneecap. Often some localised swelling can be seen, and the area is acutely tender when touched, and occasionally also has some heat over the region as well. OSD is thought to effect 10% of adolescents – that’s a pretty significant figure! But check out what one recent study showed:

OSD can impact the adolescent athlete for longer than the usual “12-18 month” recovery often stated; with one recent paper reporting impaired function at a median 4 years follow-up

In another study, a group of children diagnosed with OSD were placed into a supervised program involving physiotherapy education and treatment – the program involved two phases: firstly, a 4 week period of avoiding their pain aggravating activities and sports, along with a structured leg strengthening program completed at home; and secondly from weeks 5 – 12 a graduated return to sport program in conjunction with progressive home based leg strength exercises. The outcome of this study showed:

- 80% of adolescents reported a successful outcome (“improved” or “much improved”) at the 12 week mark.

- 16% returned back to sport at 12 weeks post intervention (but this figure increased to 67% by 6 months).

With only 1 in 6 returning to sport at 12 weeks when on an excellent physiotherapy education and management program, you’d hate to think of the pain and difficulty for those kids who are self managing their “growth pain” in the hope that it will “burn itself out”.

The other growth-related condition commonly seen is (strangely enough also termed a “disease”) Sever’s Disease – better termed Sever’s Condition. Like OSD, Severs Disease (SD) occurs in children (slightly younger on average than those who develop OSD) and is characterised by acute local pain and ache around the back of the heel. Growing children have normal developmental outgrowths of bone at the knee and heel respectively. These outgrowths of bone are ossification centres that eventually fuse into the main part of the bone beneath, forming one solid bony structure (sit with your knees at a 90 degree angle and have a feel of the bump at the top of your shin: that’s your calcified ossification centre), During adolescence and until calcification occurs, the cartilage structure that connects these bony outgrowths to the bone beneath is vulnerable to excessive forces. One of the reasons we see OSD and SD is that we have large and powerful tendons (the patella tendon at the knee and the achilles tendon at the heel) attaching right into these vulnerable developmental regions, pulling on the weaker cartilage junctions, resulting potentially in pain and inflammation.

So you can see how it is easy to palm these pains off as “growth pains” because it really is a condition that effects growing regions of bones in adolescents. And it’s also easy to go with the strategy of “it will burn itself out” because once that growth/ossification centre calcifies, the pain will go – but do you want your child to potentially be in pain for up to 4 years on end?

There’s one other factor to mention briefly before finishing – all kids have vulnerable growth centres in the same places, with the same tendons pulling on the area. So why don’t more kids get growth related pain conditions? Without doubt the most common factor (but certainly not the sole factor) we see in the cause of growth-related conditions is excessive loading activity. I’m not joking when I say we often need an extra page in our clinical notes to list the sports and activities that some children do – school, club, representative, state, lunchtime, multiple sports, honestly the list can go on and on. I also feel that our kids specialise in sport way too young and compete way too hard from too young an age (but that’s a topic for another day also) so one of the easy things to think about as a starting point, if your child has a growth-related pain syndrome, is how much activity are they doing!

Anyway, hopefully you can see now that growing pain that burn itself out eventually isn’t as simple as it seems. And 3 or 4 visits to your local physio may help turn years of potential pain into a much more manageable and acceptable outcome! Giving advice on how much rest is necessary (and rarely do we completely cease activity), what activities to continue, what exercise are effective, and how to manage the pain and inflammation, is an area that we as physio’s can make an enormous difference in the difficult world of adolescent growth pain!

Anthony Lance

SSPC Physiotherapist

References available on request

You might like these other resources

Why Do My Joints Ache In Cold Weather?

11 June 2025

The Role of Ice in Managing Acute Sporting Injuries

17 September 2024

Are Your Bones Strong Enough?

28 May 2024